Trang Cao – Nguoi Viet NW (Northwest Vietnamese News)

Three-Part Series: Introduction

The coronavirus is a disease that kills people as much as it kills human connection. The prolonged pandemic has led to a season of separation, social distance, and isolation. As COVID-19 took the world stage by storm since March 2020, it shut down local stages for event producers, musical artists and performers. One by one, each venue closed its doors, each schedule show cancelled, every event postponed indefinitely. It’s been five months. There’s no end in sight yet.

Those in the world of performance arts and entertainment face a particular challenge: they struggle without the established venues and stages to engage their audiences and make a living. Some moonlight performers are fortunate enough to have day jobs to turn to: local Seattle singer Đoan Trang continues to work for the post office; Thùy Trang keeps rocking her job at Boeing; Phan Vũ Ngọc of Band Vietstarz supports his family working at Nordstrom. Others have had to halt activities completely. Then there are some artists working to find paths forward, to reach their audiences in lively, new ways. If COVID-19 is a social disruptor that exposes the instability of our existing structures and automated behavior, it also presents opportunities to revitalize relationships and revision new modes of engaging.

This three-part series features the stories of four unique figures in the Vietnamese arts and entertainment landscape—against the backdrop of Covid-19: A celebrated 40-year veteran master of ceremonies whose lifelong approach and offstage work shows him to be a trailblazer in many ways; a husband-and-wife creative production team who are the youngest talents to steer Asia Entertainment in new directions since they joined forces in 2014; a famed musician, whose absence from the music scene for over 20 years only makes his return to us in the Covid season that much sweeter.

If the virus is a killer of body and spirit, then the works of these people strive to enliven through immediacy, closeness and connection. The people featured in this series are each warriors in their own right: they’re combatting the death and disconnections, made more apparent by the coronavirus, in their own ways. Their mediums of music, film and storytelling strive to build a sense of community and bridge cultural gaps in a fractured world. While some of them were moving in this direction before the pandemic hit, this extended quarantine has made it clearer: they can’t continue the work they were doing before using old forms, tenors and vehicles. They cannot rely on big productions and live stage events. They have to build more agile platforms to engage, and find more vital ways to create closeness in an age of social distance.

MC Việt Thảo has always walked the line between the formal and the folk, the elevated and the accessible, with incredible ease. A mix of eloquent, thoughtful address to his audiences and off-the-cuff quips show his warmth, wit and comedic charm. To watch even a handful of his massive body of work over the past 40 years is to know: Việt Thảo has a distinct ability to draw people closer. His open and affable approach makes us feel instantly welcomed and invited to participate in something special—from banquet hall weddings, to church benefits, to the building of temples, to big stage productions of giants like Thúy Nga, Asia Entertainment, and Vân Sơn (for whom he was the veteran host for almost 20 years). To my knowledge, Việt Thảo is the only MC to have hosted his own Tonight Show to rival those on American broadcast television.

MC Việt Thảo has always walked the line between the formal and the folk, the elevated and the accessible, with incredible ease. A mix of eloquent, thoughtful address to his audiences and off-the-cuff quips show his warmth, wit and comedic charm. To watch even a handful of his massive body of work over the past 40 years is to know: Việt Thảo has a distinct ability to draw people closer. His open and affable approach makes us feel instantly welcomed and invited to participate in something special—from banquet hall weddings, to church benefits, to the building of temples, to big stage productions of giants like Thúy Nga, Asia Entertainment, and Vân Sơn (for whom he was the veteran host for almost 20 years). To my knowledge, Việt Thảo is the only MC to have hosted his own Tonight Show to rival those on American broadcast television.

A master among masters of ceremonies on all the world’s stages, Việt Thảo is now accomplishing something rare and unexpected on the small home screen: he is tending an archive of our hopes, fears and appetites. Việt Thảo’s robust collection of “Chuyện Bên Lề” [Side Stories] published on his YouTube channel, creates a folk space for the lost art of simple sharing and intimacy. As the title suggests, “side stories” are a colorful mosaic of little paths less tread; not mainstream traffic. The stories can be grouped into three broad themes: ghost stories, food stories, and Việt Thảo at large (or on the roam). These stories form a rich catalogue of the experiences of Vietnamese community at home and abroad.

The format is beguilingly simple—and surprisingly captivating. With the ghost stories, people write to Việt Thảo, send him their paranormal stories as experienced firsthand or by someone close to them. He reads them aloud, amplifying the author’s experience through his own voice, drawing an audience into the story circle. This echo-chamber between writer-reader-audience gives each personal tale more resonance, extended life. In the episodes on cuisines, Việt Thảo places a steaming dish he has just cooked up before us, then proceeds to savor it with lips-smacking gusto as he describes its flavors, aromas, ingredients, and origins. We watch, salivating, because we have eaten versions of these very dishes before, prepared by our mothers or grandmothers. Through this vicarious sharing, Việt Thảo invites us to “cùng ăn và cùng thèm” [eat together and crave together]. But it’s more than just the food we crave. Việt Thảo pairs the ingredients of food with cultural history, people and place to touch his audience viscerally. One memorable episode of Việt Thảo on the roam shows the grown man with a child’s glee as he picks wild blackberries from thorny bushes on the side of a road in Washington State. The audience watches him pop one berry after another into his mouth with simple joy, perhaps recalling an August summer of their own childhoods.

The seemingly simplistic form, content and approach is a foil: Việt Thảo is a master of creating intimacy. His work actually provides several important social services we’ll explore in the feature story on him. For one, Việt Thảo’s side stories, in content and length (between 30-60 mins each), insist on a slowing down, taking time to sit with someone, to listen. They create a sincere shared space of everyday experiences in our modern world of short attention spans, flash sentiments and rushing around. In the feature on this beloved figure we learn more about his dedication to the service of his audience. (Faithfully, he reads and records a new story for his audiences every night at 7pm). We also examine the role his stories play in their lives. A closer look at his approach to voice, language and storytelling reveals what makes his work particularly relevant in this Covid season, and beyond.

Hoàng Đăng Minh and John Bạch are each creative heavyweights in their own right. She has a background in global reportage and documentary filmmaking; he, in broadcast journalism and music production. Combined, they are a revitalizing, behind-the-scenes force rarely seen but steadily shifting the monolithic Asia Entertainment in new directions. Barely into their mid-thirties, the creative producer/director team have inherited quite the legacy.

Hoàng Đăng Minh and John Bạch are each creative heavyweights in their own right. She has a background in global reportage and documentary filmmaking; he, in broadcast journalism and music production. Combined, they are a revitalizing, behind-the-scenes force rarely seen but steadily shifting the monolithic Asia Entertainment in new directions. Barely into their mid-thirties, the creative producer/director team have inherited quite the legacy.

Asia Entertainment is not just a music production house, it’s a cultural juggernaut. It was born 38 years ago in 1982, in a recording studio in the garage of John’s grandfather, the prolific musician Anh Bằng, in Garden Grove CA. (The family moved there after immigrating to the U.S. as boat refugees and calling Tacoma, Washington home for the first two years). From a makeshift cassette recording studio, Asia grew into one of the biggest, most beloved music production houses of its kind, to rival Thúy Nga and Vân Sơn. Under the direction of singer Thy Vân, Anh Bằng’s daughter, after 1992, Asia has produced 396 CDs and nearly 100 DVDs based on their recorded concert series, launched dozens of careers, and boasts over 300 artist collaborations. Asia not only filled a cultural void for the community of southern Vietnamese living abroad as a result of fleeing Vietnam after the war, it became an archive, a museum, of Vietnamese cultural consciousness and nostalgia. As such, there was heavy emphasis on Nhạc Vàng [Gold Music], made popular in 1960s prewar South Vietnam.

Đăng Minh was brought on in 2012 to conduct behind the scene interviews, edit and produce documentary videos she had earned a reputation for with her reporting work at SBTN (John was her cameraman then, and they would hunt down stories together). In 2013, Asia was the only one doing this kind of behind-the-scenes storytelling. This move showed great foresight on Thy Vân’s part: the documentaries were a thoughtful counterpoint to the glossed and polished acts of the stage performances. They brought a real-life complexity and human dimension to the well-rehearsed stage acts, and paid attention to the creative process, not just the finished product.

Asia had a found a successful formula in those direct-to-video music programs: an elaborate spectacle of dozens of big-name performers acting out the music they had prerecorded, against a backdrop of epic grandeur, in a several hours-long ceremony hosted by charismatic MCs in a vast auditorium before a formally invited and seated audience. Classy, clean and civilized. This format has been the model workhorse of iconic production houses like Thúy Nga (Paris by Night) and Vân Sơn for decades—but it had grown tired after so long. John Bach and others will admit that these shows are in some ways “glorified music videos.” In recent years it had grown obvious: there was disconnection between the audience and performers, as well as the original, lively spirit of the eras in which those songs were born.

Since working together on Asia 69, Đăng Minh and John Bạch have been working to inject liveliness into classic Vietnamese golden oldies and stage shows in distinct ways, as we explore in their feature story. Their goal: bring audiences closer. They have directed and produced three programs together from concept to finished product, including the thoughtful behind-the-scenes making of how these projects evolved. Asia Icons: Mai Lệ Huyền (2014); Asia Golden 4: Khúc Nhạc Tình Quê [Homeland Love Songs/Village Love Songs] (2015); and Asia 79: Còn Mãi Trong Tim [Forever in the Heart] (2017) (perhaps also Asia 77: Dòng Nhạc Anh Bằng & Lam Phương [The Music of Anh Bằng & Lam Phương] to some extent) have the signposts and earmarks of their evolving vision for the path ahead.

A rendition of “Vó Ngựa Trên Đồi Cỏ Non” [Horse Hooves on Tender Grass Hill] (performed by Thế Sơn in Khúc Nhạc Tình Quê) comes to life with a gritty edge thanks to collaborations (with Brian Morales) on new musical arrangements, cross-cultural influences (think Ennio Marcone’s scores of spaghetti western films), and live band instrumentations. Paying special attention to the temporal and spatial quality of the original song, they evoke an atmosphere of the old west outlaw, the lone cowboy, moving with purpose and consequence with a gallop of taut bass and drums, some dirty brass wailings, dramatic guitar pulls, and twangs of the Jew harp. They accomplish what the song’s closing lyrics of redemption suggests: “Em hãy theo anh, men lối ăn năn / Ta thoát cơn mê cùng dắt nhau về” [Follow me, leaven paths of repentance / We escape the nightmare and carry each other home]. The live performance tributes to the “Queen of Rock” Mai Lệ Huyền, with the juicy sounds of 50s, 60s and 70s big band and multicultural influences, provides even more powerful example of where and how they’ll be directing their energies to shake things up and bridge the generational gaps.

What we learn from talking with them is that something remarkable has been lost in translation, dulled by repetition. The need for more direct interaction, immediacy, liveliness and connection is, above all, the call to action in the Covid season. Đăng Minh and John Bạch offer insights into this moment of cultural shift, for Asia and for other artists who care about cultural revival and innovation. Our conversation with them reveals the kind of negotiation, passion and care it takes to steer a massive ship in new directions and towards new generations of Vietnamese music appreciators.

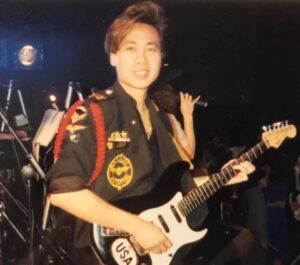

The name Quốc Sĩ and The Magic band is not foreign to any true music enthusiast in the Vietnamese transnational community, and especially to those in Seattle, where every one of their shows was sold out, and where, he admits, the liveliest, most ignited performances of their lives took place. Perhaps there is no musician of any Vietnamese band that has performed more live shows, more widely-travelled, than Quốc Sĩ. At the peak of their fame from the mid-80s to mid-90s, Quốc Sĩ, Như Mai and The Magic band were performing at least three live shows a week, every week except for major holidays, traveling from state to state across the US, and flying all over Europe (France, Germany, Czech Republic, Netherlands), Australia, and Asia to hordes of screaming, adoring fans. The band burst onto the scene as a New Wave sensation, then later went on to perform genres that ranged from classic rock and roll to love ballads for the homeland. They were a rolling fireball that showed no signs of stopping. Then suddenly, they dropped off map at the height of their fame. We explore the reasons that led to this more deeply in his story.

The name Quốc Sĩ and The Magic band is not foreign to any true music enthusiast in the Vietnamese transnational community, and especially to those in Seattle, where every one of their shows was sold out, and where, he admits, the liveliest, most ignited performances of their lives took place. Perhaps there is no musician of any Vietnamese band that has performed more live shows, more widely-travelled, than Quốc Sĩ. At the peak of their fame from the mid-80s to mid-90s, Quốc Sĩ, Như Mai and The Magic band were performing at least three live shows a week, every week except for major holidays, traveling from state to state across the US, and flying all over Europe (France, Germany, Czech Republic, Netherlands), Australia, and Asia to hordes of screaming, adoring fans. The band burst onto the scene as a New Wave sensation, then later went on to perform genres that ranged from classic rock and roll to love ballads for the homeland. They were a rolling fireball that showed no signs of stopping. Then suddenly, they dropped off map at the height of their fame. We explore the reasons that led to this more deeply in his story.

At a time when the pandemic has closed off all stages and performance doors to artists—and when many have taken a long pause—Quốc Sĩ has found a means to return to audiences again, in a most tender, unexpected way. After being absent from the music scene for over twenty years, Quốc Sĩ and the Magic are now releasing videos on YouTube of the songs they themselves have written, arranged, performed and produced. This is a vulnerable move that shows tremendous courage. For one, there is the ghost of their past and reputation that they have to either banish, in some ways, or live up to. Secondly, the Vietnamese convention seems to be that there are songwriters, there are singers, and there are musicians; rarely do the three manifest as one. The singer-songwriter-musician is a rare bird.

Now in the Covid season Quốc Sĩ is showing up in intimate new ways and dimensions. He’s written eight new songs, with powerful, poetic lyrics that he delivers with the rich timber of his voice and melodic live instrument playing. More interestingly, these songs speak to our moment of crisis: the uncertainty and isolation caused by covid-19. He’s using YouTube as platform, not to monetize his music, but to create connection in a moment of great disconnect. His song “Bàn Tay Nhân Ái” [The Hands of Compassion] was released in May 2020 on the YouTube channel of his brother and band member, Tommy Nguyen (Nguyễn Duy Tường), and already has over 11,000 views. It is one of the first songs to ever be written explicitly about those at the frontlines of the coronavirus war. One of the other songs, “Ngòi Bút Đam Mê” [Passionate Pen Tips], is perhaps the first of its kind also: it pays tender tribute to those who choose the pen (reporters, journalists, writers), as their weapon against sleep, apathy and injustice in the world.

Our conversation with Quốc Sĩ offers vivid insights into moments of cultural connection and disconnection as the Vietnamese-abroad music scene evolved. Quốc Sĩ has a unique long view; he’s a veteran of cultural growing pains. He’s got a long range, from performing in the very first night club for the Vietnamese community in Orange County, CA with those musicians who are now big household names, to the rowdy night clubs of New York City, and then the stages of Paris with major productions like Thúy Nga, and all over the world wherever there was a transnational Vietnamese community. The Quốc Sĩ of this moment signals new and perhaps more authentic ways that Vietnamese artists might engage with their audiences. He offers perspectives on this moment of deep pause the world has taken, and how it might just be the wake-up call me need to connect more authentically.

What’s clear from our conversations with each of these talents is that there is a civic dimension to the work they do, and continue to do, despite the pandemic. We learn there are ways that artists can do disservice to their audiences, and opportunities they can pay them greater tribute. These stories also underscore the call for the audience to not just be passive consumers of culture, but active participants in its making. These artists’ stories point to trends in transnational Vietnamese cultural productions and contestation in a reimagining of the artist-audience relationship edged on by the context of Covid-19. This moment of disruption and disconnection offers an opportunity to reassess the ways we can engage in the world more intimately. Join us in exploring these stories further.