Trang Cao, PhD – Nguoi Viet NW

– Three-Part Series

3/3: Quốc Sĩ Keeping The Magic Alive – With Tenderness

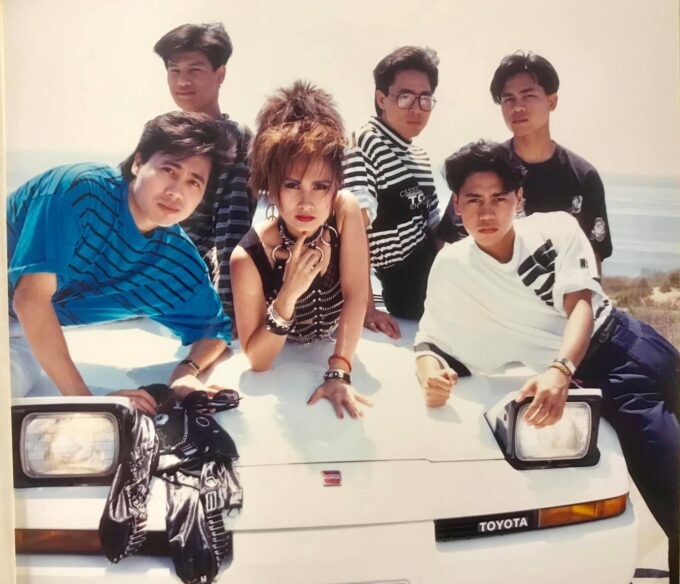

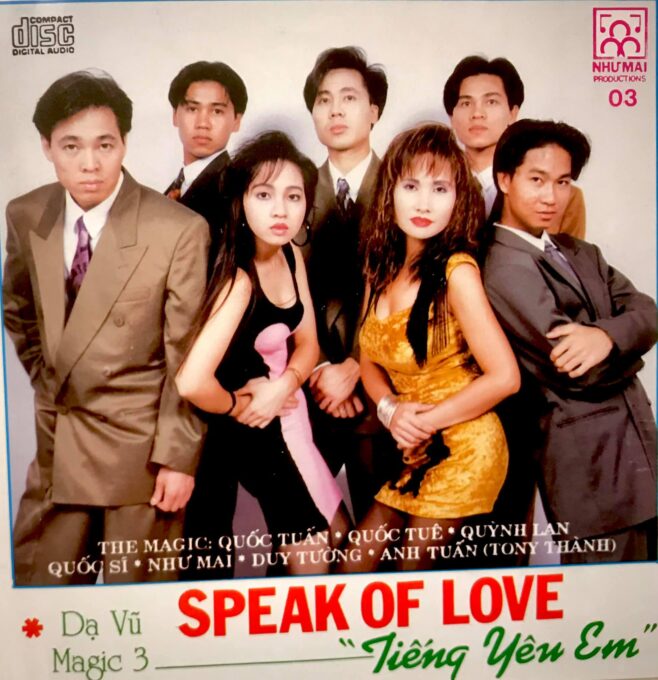

Perhaps there is no musician of any Vietnamese band that has performed more live shows, and is more widely travelled, than Quốc Sĩ. At the peak of their fame from the mid-80s to mid-90s, Quốc Sĩ, Như Mai and The Magic band were performing at least three shows a week, traveling from state to state across the US, and flying all over Europe, Australia, and Asia to hordes of screaming, adoring fans. Except for Quốc Sĩ and Như Mai who were in their early 20s, the other original members, comprised of Quốc Sĩ’s younger brothers, were teenagers (then 18, 16, and 14). The band burst onto the scene as a New Wave sensation, then later went on to perform genres that ranged from classic rock and roll to love ballads for the homeland, always with their poppy electronica twist. They were a rolling fireball that showed no signs of stopping. Then suddenly, they dropped off map at the height of their fame

At a time when the pandemic has closed off all stages and performance doors to artists—and when many have taken a long pause—Quốc Sĩ has found a means to return to audiences again, in a most tender, unexpected way. After being absent from the music scene for over twenty years, Quốc Sĩ and the Magic (now composed of his brothers Quốc Tuấn and Quốc Tuệ) are slowly releasing videos of the songs they have written, recorded and produced themselves on YouTube. This is a vulnerable move that shows tremendous courage. For one, there is the ghost of their past fame and reputation that they have to either banish, in some ways, or live up to (fans associate The Magic with Như Mai and some accept no alternative formation). Secondly, the Vietnamese convention seems to be that there are songwriters, there are singers, and there are musicians; rarely do the three manifest as one. The singer-songwriter-musician is a rare bird, but an easy target. Finally, these songs speak to the experiences of separation and loneliness in our current moment of social crisis.

Quốc Sĩ is no stranger to loneliness and isolation. At 17, he became an accidental boat refugee. It was 1977 on a Saturday night. He was hanging around a cove at the beach in Vũng Tàu when he came upon a fleet of people about to escape Vietnam by boat. They couldn’t risk him telling others, so he had two choices: get aboard or get shot. His mother sobbed for weeks as if her entrails had been cut. Her firstborn son had vanished without a trace. He could not get news to his family for three weeks. He was supposed to become a catholic priest, or at least that was the plan. His father had placed him in a seminary at the age of 10 and he had a bright and promising path of service to god laid out before him. Life had other plans. After a brief stay in the Malaysian refugee camp on Pulau Tengah, the UN Commission located an uncle in California and Quốc Sĩ departed for a strange new land.

Soon, however, the uncle moved away and Quốc Sĩ stayed on his own, sharing a room with a friend, going to high-school, then trade school, and working graveyard shifts at Jack In the Box to send remissions to his family. They were “my singular beacon of hope,” he tells us. The idea of being with his family again kept him going. He also recounts many Tết spent completely alone in his room, in the winter. A friend came by and gave him a pack of instant noodles; he’ll never forget that gesture. Thanks to the help of Đỗ Hữu Liêm, whom he calls “my family’s benefactor, in some ways,” he was able to share a room of a house owned by the well-known lawyer and sponsor his family to the United States, one by one. The first to come was his brother, Quốc Tuệ. Quốc Sĩ admits he’d never known a moment of greater happiness in his life—to finally have family again after years of being alone.

Quốc Sĩ found solace in music a few years after immigrating to US. He had learned to play guitar (secretly) when he was in the seminary, but it didn’t take hold until he arrived in the US. It was a way to abate loneliness. By the early 1980s he got gigs playing bass and guitar for some of the first Vietnamese music venues and connected with other Vietnamese artists around shared songs and language. The Orange County Vietnamese music scene was undeveloped then. Immigration and the struggle of finding roots in a new land created a cultural void. The first tea room in Orange County, Làng Văn, was the first of its kind, and the first to host live music. Afterwards, Café Lam would follow suit. Because there was essentially nowhere else for Vietnamese to congregate, they would flood to these places after work and on weekends. These live music venues created a space for them to connect with their countrymen and revive a culture. Quốc Sĩ played bass to the guitar of musician Trần Ngọc Sơn (son of musician Anh Bằng) seven nights a week to support his family (who were all in high-school then).

Music also kept his family together. Quốc Sĩ describes the environment of Orange County at that time as being like the 1980s Chau Yun-Fat Hong Kong television series, “Blood Stains the Shanghai Quay” [Máu Nhuộm Bến Thượng Hải]: gangsters, guns, bravado. To keep his siblings from falling into thug life, he formed a family band and had them practice instruments from morning until night on the weekends. “The Magic” was inspired by the 1982 song by America, “You Can Do Magic.” Quốc Sĩ hoped to inspire them to make magic with music instead of getting into trouble.

In November of 1986, the chance cancellation of a big-name band just days before a show was set to go on a stage in New York led to a “golden opportunity.” Quốc Sĩ pitched his family band as stand-in. The manager was hesitant, but had no choice and no time to find a replacement. When the manager finally met the band members at the airport, he was shocked to discover they were just scrawny teenagers. He thought the show was dead in the waters, but Quốc Sĩ, Như Mai and The Magic were a daring, surprise hit. News quickly spread like wildfire about their youthful energy, and their tight, vibrant sound. The bookings poured in from all over the United States, and later across Europe, Australia and Asia, wherever there was a Vietnamese diaspora. They played with musicians that have since become household names in the Vietnamese musical pantheon, such as Ngọc Lan, Kiều Nga, Trang Đài, Tuấn Vũ and others. They became stars themselves. They went from performing in the tea rooms and cabarets to night clubs and then big stages of iconic production houses like Asia Entertainment and Thuy Nga’s Paris By Night. (The Magic appear in several Paris By Night shows, including #13, the “Special Edition” to challenge superstition).

Still, Quốc Sĩ recalls more vividly the livewire energy of those early days performing small shows; it’s revealing. Unlike the later big-stage shows of major production houses with a parade of performers and polite, seated audiences, the small shows featured just a handful of singers, a live band and a small audience (maybe a couple hundred) in attendance. But those small shows, Quốc Sĩ tells us, “were more raw and alive.” Performers had direct interaction with the audience and they fed off each other’s energies. Of all the cities they’ve performed, Quốc Sĩ tells us, “Seattle is still our absolute favorite.” Why? “The fans there loved us, they were alive, and they would go crazy.” In turn, the band would give them the best performance of their lives. Drum solos that were so furious they broke the drum skin. Clothes came off. Extended guitar solos that ignited the audience, erupted in sobs, and made Quốc Sĩ feel as though he would “burst into flames.” There was a most direct live-feed between the performers and their audiences in Seattle.

At the height of their fame in the mid-90s, the band suddenly stopped. Rumors and scandal swirled around them. This included whatever ills you could image: Quốc Sĩ was a cocaine addict, a depraved sex addict, a tragic victim of aids… In truth, life had become too chaotic and three reasons led to the band’s decision to stop: 1. Như Mai (considered the soul of the band) left and pursued a solo singing career (she and Quốc Sĩ divorced also); 2. his brother Duy Tường was diagnosed with leukemia and the doctors gave him three months to live (Duy Tường fully recovered eventually, thanks to a bone marrow transplant from a sister they had to bring over from Vietnam to save him); and their second drummer passed away from throat cancer. The heartbreak, struggle, and despair led the family to say “enough.” The band split up, went separate ways to tend their lives offstage and focus on things that mattered to them.

From 1995 to 2015 it seemed Quốc Sĩ had entirely disappeared from the music scene. In a way, he had returned to the convent path he was on in his early years, when he was preparing for a monastic life. In this period of silence, Quốc Sĩ worked on realigning his energy and successfully studied Qigong for over ten years. He opened a furniture and décor shop, led a simple life and even got married again. He would play shows for church benefits to fundraise and help those less fortunate in the Vietnamese community, or play at dance studios for people to practice, but mostly, he stayed away from the spotlight.

Now in the Covid season, Quốc Sĩ is showing up in intimate new ways and dimensions. He’s written eight new songs, with powerful, poetic lyrics that he delivers with the rich timber of his voice and melodic instrumentation. More interestingly, these songs speak to our moment of crisis, the uncertainty and isolation caused by Covid-19. He’s using YouTube as platform, not to monetize his music, but to create compositions. Quốc Sĩ admits he’s had to overcome the fear that his own compositions “weren’t good enough.” The Vietnamese convention is to sing or perform the songs others have written.

“If The Magic were to return to the public stage,” Quốc Sĩ tells us, “we would perform the songs we wrote. We would play our own instruments, do our own singing. Perhaps I wouldn’t be as good a singer as others, but at least I would be singing my own songs. There is something honest about that.” Quốc Sĩ notes the need to inject real feeling back into musical performances and do away with lip-syncing performances (of big stage shows). For him, unfiltered performances are more authentic musical experiences though they may be unpolished.

His song “Bàn Tay Nhân Ái” [Compassionate Hands] was just released in May 2020. By August 20, 2020, Asia Entertainment released a video with the singer Melanie Nga My performing the song, with over 97,000 listens in just 20 days. “Compassionate Hands” is one of the first songs to ever be written about the coronavirus explicitly, and it’s a moving tribute to the warriors at the frontlines of the pandemic. The song draws on the loneliness of struggle and separation between panes of glass, of doctors and nurses, “those angels in white,” bravely risking their lives to care for those fallen sick from the virus. But it is not only the nurses and doctors who are angels. The song suggests that every person who thoughtfully made protective gear for others also sewed their healing intentions into those masks (like the local Seattle musician, Phan Vũ Ngọc of Vietstarz band and his wife, who sewed 3,000 masks at the beginning of the pandemic to give away to people who didn’t have any.)

từng đường kim em khâu, em mong lành trái tim

từng đường kim em đan, em mong lành vết thương

và từng câu kinh đêm, xin ơn lành xuống ân, xóa hết bao khô đau…]

[every needle stitch I sew, I hope to heal the heart

every needle stitch I knit, I hope to heal the wound

And every night prayer, I ask grace to descend, erase all the pain…]

The image of the needle point stitching the line of thread, as doctors would stitch a wound close to heal, is striking. The sharp and the tender. We only begin to mend when we think of others. This is how Quốc Sĩ sews himself into the hearts of listeners also, tenderly, thread by thread. In this “season of isolation” [mùa cách ly], everyone has to stay away from each other and stay apart. But that song suggests “we distance to know closeness” [xa cách để biết thân]. According to Quốc Sĩ, “we need to grow closer, to hold each other, sit together, hold each other’s hands. We get closer by sharing” [gần gũi nhau bằng cách chia sẻ], and that’s the only way we can get through this.”

Quốc Sĩ reflects on what the pandemic has given us, aside from great sorrow: “People are becoming closer in this Covid season, learning to love each other more. Because they’ve had to pause, take stock of what’s important. There’s a feeling like life is not just the squeeze [bon chen], not just the hustle and bustle [xô bồ], not just the rush [hối hả] to find money, luxury [xa hoa], fame [danh vọng].” He remarks on the ephemeral and illusory nature of all material things: today’s empire, tomorrow’s ashes in a blink of an eye. The song lyrics of “Dear Father” [Cha Dấu Yêu] comment on the transient of life as we forge our paths in the world: “the shadow faded away, I left each prodigal day” [hình bóng xa mờ khuất, con đi biệt từng ngày tháng hoang đàng].

In “Mother’s Letter” [Lá Thư Của Mẹ], Quốc Sĩ employs striking images to evoke a sense of heaviness, and how it is hard to move sometimes inside the urgencies of time and distance:

chiều hôm nay bỗng như vắng lặng

hàng cây khô đứng im cúi đầu

rồi mai đây xa cách muốn trùng

cầu mong con nhớ lời mẹ khuyên

[this afternoon suddenly silent

rows of dried trees stand still, head bowed,

then tomorrow the distance wants to coincide

May you remember mother’s advice]

He combines images of the vast and the small to signal eternal closeness even in separation. In the song, each of the thousand stars in the night sky become a final kiss.

vầng trăng khuya tối nay sắp tàn

ngàn vì sao khuất trong bóng đêm

mẹ yêu con, yêu nhất trên đời

mẹ hôn con một lần mẹ đi

[the late moon is about to fade tonight]

a thousand stars hidden in the dark

I love you the most in the world

I kiss you once more and then I depart]

Quốc Sĩ tells us, “Covid is a bell calling us to consciousness.” This is, “if people just calm down, pause and reflect. Be still a moment. Sit together a minute. People are rushing and rushing around, but where are they going? Time passes by them and then they realize they’ve gone nowhere at all. People are realizing that there are things more important than money, material, industry. There’s love and people being with each other heart to heart.”

Quốc Sĩ is a person of feeling. “Like my mother,” he said. His return to music at this moment is a compassionate choice: there’s a need for songs, closeness and sharing. If “sound, voice, and music are also forms of healing,” then the musician has a call to the front lines as well. Quốc Sĩ composes to share in the collective experiences and our private wars. The songs speak to more general experiences through the language of intimate relationships.

When asked if he would consider livestreaming performances in the near future, he gets bashful. “Audiences are used to seeing the formal standing performances of Thuy Nga or Asia. I’m not sure they would enjoy seeing me sitting in my studio and playing directly for them in such a simple way.” I would argue that audiences perhaps need to learn that there’s space for the more direct human interfaces and engagement in music, especially now, when musicians have to step off the stage and into our hearts more authentically.

Trang Cao, PhD

Read this article in Vietnamese