Virtual teaching and learning during the Covid-19 pandemic is changing the curve of higher education. Vietnamese professors share their experiences and reveal the potential future of adapting education to diverse needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education systems in history, affecting nearly 1.6 billion learners in more than 190 countries and all continents. This disruption has transformed the way students access education and the way teachers adapt instruction — but will it lead to more enduring, equitable shifts in our educational system?

Back in the spring when Covid-19 was emerging around the world and leading to widespread shutdowns, schools at all levels had to adapt quickly. Students were sent home. Schools and campuses closed their doors. Classes went online. Whether or not they were comfortable with video conferencing apps like Zoom or other instructional technology, everyone tried their best to adapt to new models of distance-teaching and learning. Teachers echoed a common remark: “My workload tripled.” One teacher tells us, “There were weeks that I averaged 14-hour days plus additional hours on Sunday. It was exhausting.” Teaching remotely is so different than running a hands-on class. Every assignment had to be reimagined and modified to drastically different format. New routines had to be established as well as new skills for everyone, from the technical to the social and the pedagogical.

Virtual classrooms were supposed to be stop-gap measure. Nobody anticipated this forced social experiment to continue for this long. But schools finished out their spring semesters online and students celebrated virtual commencements. Quyen Di, head of UCLA’s Vietnamese language program, delivered his congratulatory speech to new graduates standing in their kitchens and living rooms instead of being capped and gowned on a stage. Now, well into the fall of the pandemic, students are still streaming seminars from their kitchen or bedrooms with cohorts in all different places. Faculty members can now hold teaching appointments at more than one university and virtually attend professional development programs they couldn’t before, due to lack of time or funding for travel. The shift to online education during COVID-19 has opened up new channels for both teachers and students to rethink teaching and learning models, but not without posing distinct challenges.

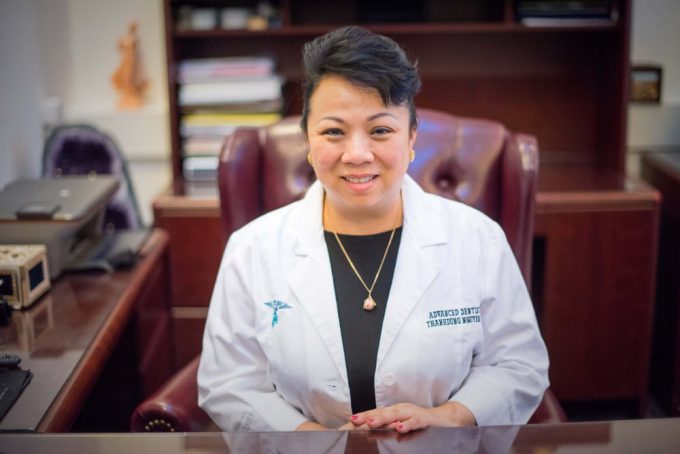

To be expected, students and faculty in disciplines that require technical, hands-on training experienced more significant challenges than others. Rochelle Nguyen, Clinical Faculty at the University of Washington School of Dental Medicine who teaches third and fourth year dental students, found that it was difficult to acquire enough patients for students to do their competency exam prior to national board examination, and to fulfill the clinical requirements for graduation. Stricter health measures limit the amount of patients that can be seen in the clinic at a time, and each patient needs to be interviewed and screened before they can enter. Patients are also more hesitant to come into a clinic because of exposure risks, making it more difficult for dental students to gain the hands-on experience they need. This is on top of the stress and anxiety of higher infection risks as they have to interact closely with patients’ oral cavities, an area known to be vulnerable to the virus.

Adaptive technology has helped in some ways. The School of Dental Medicine developed a teledentistry program and adopted a hybrid model of attendance: students can attend lectures and study materials online, but they are still required to come in for clinical rotations in order to gain hands-on experience. Until virtual dentistry advances further, perhaps with VR technology, nothing can replace that kind of personal hands-on training. Technical difficulties can also disrupt the virtual classroom when staff are not IT savvy or trained to troubleshoot issues, and students have varying levels of ease and access to technology.

For some teachers of other technical disciplines, the sudden move to virtual education presented new opportunities. When it was clear that he would not be delivering fine art instruction in the classroom this fall, Trung Pham, artist, theologian, and professor of art and art history, embraced the challenge. Rather than balk at the difficulties of teaching painting or sculpture via video livestream, he found new tools for connection and creativity. He did not simply deliver his usual instruction within the limitations of Zoom; he reimagined the art-learning experience and completely redesigned courses with more immediate, interactive tools. He tells us, “One sure thing I’m learning from this pandemic is that no one nor force can stop human connection and creativity…some might agree, the pandemic might shut the front door, but it also encourages us to open other windows.”

Trung Pham now conducts online mass for youth. His virtual congregation is only limited in size by server capacity. During the course of this pandemic, he simultaneously taught theology at Seattle University and art and design courses at Grünewald Guild. He learned a few things in the process. Trung Pham diverged from his traditional fine art discipline of strictly using material media and taught himself a whole new suite of art tools in Procreate, a digital illustration app for iPad. Thanks to the free aid of YouTube video tutorials, he adopted new skills over the course of the summer in order to teach his students the principles of art-making using these new applications in the fall. His graphic arts and illustration classes were a hit with students, enabling them to draw, paint, and even animate their creations; his 3D modeling class even more successful as students could inspect their building and sculpting projects, turning objects this way and that to gain perspective in real-time.

Although the learning media and platforms are different, he tells us, the core principals remain the same: “Art and ideas can exist and live in different settings, and digital platforms open up new spaces for creativity.” Digital tools have allowed his students to express ideas with immediacy, while mastering traditional principles of art-making. Students also gained new ways to share their work that they could not do so easily with traditional media. Rather than exhibiting in physical galleries, they can now exhibit in virtual galleries and share their work instantly on social media. For a trained artist like Trung Pham, traditional material art will always hold a special place. But he sees art and its instruction moving to digital platforms as a positive shift from a space of exclusivity and commodity, to a space of wider sharing and communication. In some ways, digital media makes art more accessible: it blurs distinctions between “high art” and other forms considered “low art” in the aesthetic hierarchy. Trung Pham sees how digital media and tools can democratize creativity and art-making, as well as education.

The shift to online teaching and learning during the pandemic highlights questions of access in higher education. Would students have to pay more to take courses online from esteemed universities? If the COVID crisis is opening new spaces for accessing education, it can also exacerbate preexisting disparities and create barriers for those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. Several professors voice concern that fully online models of education can worsen existing inequalities — such as who has access to the technology, resources and conditions for remote and more independent learning.

Tam Dinh, professor of social work and program director at Saint Martin’s University in Lacey Washington saw students face extreme difficulties shifting to remote education during Covid-19. “Many students did not have the proper technological equipment or access to wifi. In addition, the wide-range of instructional delivery models, inconsistencies of teacher-student engagement, and abrupt social disconnection with peers have led to increased anxiety, isolation, and depression…At the K-12 level, the shift to more parent-guided instruction has negatively impacted students from families with limited English capacity, students with two working parents, students from families with limited incomes, and students with learning challenges.”

While the department of social work prepared their students well for the transition to online learning just before the shelter in place ordinance hit, students still had issues adapting to some of their other classes. Teachers use a wide range of technology platforms with inconsistent instructional delivery methods that can create non-cohesive class expectations. Besides adapting to new academic norms, students were also dealing with many COVID-19 related issues, such as having to move back home on short notice, increased health concerns, and more financial challenges.

Bich Ngoc Turner, Lecturer of Vietnamese in the Department of Asian Languages and Literature with the Group of Universities for the Advancement of Vietnamese in America at the University of Washington, also found that her students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds experienced greater difficulty transitioning to online learning. Most students have had to move back home and it has taken them some time to adjust. Those who live in more cramped conditions have had a hard time compromising with their household members around study spaces, shared internet use, background noise, and distractions.

Further, she tells us, “I am aware that a good number of my students come from a disadvantaged socioeconomic background, where their family members do not have the luxury of working from home, are highly dependent on the public transit system, or share households with at-risk senior family members, or live in crowded, traditional communal neighborhoods that may make it difficult to practice social distancing, therefore [making them] more vulnerable to the virus.” Restrictive living spaces and learning environments add an extra layer of stress to their experience of online education. Overall, the professors expressed greater awareness of how the pandemic has impacted students of lower socioeconomic backgrounds and minority groups more disproportionately.

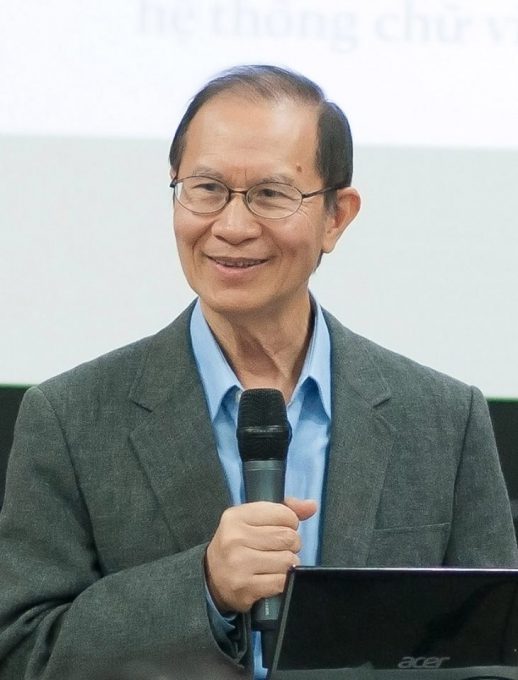

Empathy runs through all discussions. Trung Pham reveals: “Empathy informs everything, from class activities to grading, to my response to absences and how we discuss ideas…” In some ways, the pandemic has urged teachers to integrate empathy in their instructional model to consider real-life demands, family situations and different socioeconomic challenges. Tuong Vu, Professor and Chair of the Political Science Department at the University of Oregon, tells us: “We have to more flexible with course demands and pay more attention to individual student circumstances.” While applying understandings of cultural diversity and inclusion is often writ into all school mission statements, teachers now emphasize its practice with greater intentionality. Teachers are learning to be more emotionally aware and responsive, acknowledging that we are not in an ideal situation and all trying to do the best we can, with greater care for diverse circumstances.

Teachers are emphasizing compassion in their classrooms more than ever and adapting their teaching styles and structures to make space for student experiences. “Asking how they are at the beginning of class and wishing them health and safety at the end of class has become my habit, something I did less frequently before the pandemic,” Bich-Ngoc Turner admits. Trauma-informed education insists that all teachers introduce social and emotional wellness components into their classrooms. This means creating intentional space and taking time to check in and acknowledging shared and individual experiences during this time of crisis.

Tam Dinh explains: “To help my students make it through this time, I had to be more explicit and frequent in my communication; restructure my syllabus to reflect the new COVID-19 challenges; provide additional opportunities and resources for extra learning; and provide intentional spaces for more advising, processing, and community building. Being flexible, supportive, and validating students’ fears and concerns while reassuring students that we are here for them and walking along this journey together with them appeared to be helpful to students as well.”

The Vietnamese professors feel that their refugee and immigrant experiences have prepared them to meet the challenges of teaching during a global pandemic. The personal challenges they have overcome as immigrants contribute to their resilience in intense moment of upheavals. Tam Dinh reflects: “Because I have been through a boat escape, spent time in a refugee camp, and had to quickly adapt to a new culture, the pandemic was just another challenge that I knew I could overcome.” Tuong Vu adds: “I have seen worse things than the pandemic, such as war and revolution. I have developed survival skills that give me the confidence that I will also survive this pandemic.” Their hope is that their students will become more resilient and compassionate from their experience of learning to adapt in these challenging times.

Besides the distractions of COVID-related stress and anxieties, many students and faculty were concerned that online learning would flatten the learning experience and reduce the interactivity that makes classroom learning so dynamic. Teachers remarked on the ways virtual instruction “cuts off other senses” and causes both teachers and students to “miss other important learning cues.” Trung Pham explains: “Online teaching reduces modes of transmission to speaking/listening and limited visual cues. The emotional contact and connection of physical presence is missing. You are talking to a screen with many squares representing students, some with their cameras turned off. For students, watching a screen for several hours can be draining and limit the desire to engage.”

Tuong Vu tells us: “Some students enjoy learning online, but many don’t. I also prefer to teach in-person classes to online ones. I like face-to-face contacts and exchanges and find the online medium restrictive in interaction.” He explains: Discussions tend to be less fluid and more awkward in the virtual classroom and there’s a lack of face-to-face connection. For larger classes, Zoom only allows you to see 25 squares (or participant faces, if their cameras are turned on) at a time, so professors have to scroll or toggle between pages to get a total view of all the students. With virtual classes, you also lose the casual meeting in the hallways, opportunities to exchange ideas, or the after-class chat to delve deeper into a topic (students tend to depart immediately after a virtual class finishes).

The challenges of stimulating more interactivity may lead teachers to embrace new instruction models and technology functionality, including an ever-more personalized approach to each student and their learning needs. Schools that valued “active learning” in the classroom before will have to reimagine the virtual learning space to be even more so. Online chat functions and break-away discussion rooms are becoming a central component of stimulating interactivity and engagement in the virtual classroom. Teachers will have to give more focus to activities that build engagement, such as warm-up activities, reflections, chats, discussion prompts, break out rooms, and multimedia presentations. There will be a range of student ability to access and adopt technology, so teachers must also adapt courses to include a range and aid and materials to meet diverse learning needs.

Everything will have to be reworked with diverse learners in mind. Tuong Vu explains: “Instructors have to think about how students may receive or experience lectures electronically. They have to consider what kinds of homework can be applied and what forms of assignments and learning activities are more suitable for new learning media. They have to make sure their communication transmits clearly and lands in meaningful ways.” It’s important to note: virtual classes demand much more of teachers. They require more design and planning with intensive lead time, from setting up technology and loading materials, to devising dynamic new ways of delivering instruction. Nothing compares to the invigorating energy of a live, in-person classroom, all teachers admit, but improved online education models may be able to capture some of that in more accessible ways.

“Virtual education is going to be the future.” Tuong Vu forecasts. Schools like the University of Oregon plan to continue adopting a hybrid model of online and in-person classes, with a heavier lean towards virtual classes than before. He sees this as the trend for upper-level education. “Institutions and individuals have already invested so much in time, energy and technology infrastructure,” Tuong Vu reflects, “they’re going to continue to develop it.” Universities can see the benefits of offering more online classes: it makes education more accessible to more students from different geographic regions, by offering them more choices and flexibility. Hybrid education models may enable students to learn in new and different ways that better fit their diverse life situations.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have essentially disrupted an education system that has not seen much transformation in decades. As education goes virtual and teachers innovate, the quality and overall experience of online learning will continue to improve. As that happens, the traditional modes of educational delivery may be questioned in some fundamental ways. We may be on the verge of witnessing a never-before-seen level of personalization in education. Universities that can adapt will see benefits. The hope is that the shift toward more personalized and responsive online education models will improve accessibility and optimize the experience for learners in a number of ways, including cost. The confusion and chaos of online education during this pandemic may give way to more enduring changes in higher education.

“The refugee experience has led me to a deep understanding of what it means to live in-between worlds… Liminal space is one of ambiguity, disorientation and turbulence, yet its vitality has the potential of transformation and growth.” This statement is part of Trung Pham’s artist statement on a series of paintings exploring the creative potential within the often painful thresholds between “what was” and “what’s next.” It also aptly captures this moment of flux for both students and teachers in upper-level education, perhaps ripe for disruption. There may be no going back to pure physical classroom-based education after the pandemic ends. The liminal space created by the COVID-19 pandemic has created room for more responsive and adaptive education.

Trang Cao, PhD.