I get to celebrate two New Years annually.

There is Jan. 1, the first day of the Gregorian calendar year. And then there’s Lunar New Year, which falls on the first day of a calendar that follows the cycle of the moon, usually sometime between late January to mid February.

Lunar New Year is celebrated across different Asian cultures, each with their own set of traditions. Note: Please don’t refer to Lunar New Year as “Chinese New Year” unless you’re talking to someone who is Chinese. In Vietnam, where I was born, Lunar New Year is called Tết and it has the same significance of Christmas and New Year combined in the U.S.

Vietnamese distinguish the New Years by referring to Jan. 1 as Tết Tây (Western New Year) and Lunar New Year is Tết Ta (Our New Year). How the holiday is described in different languages reflects its relativity.

How I have learned to celebrate Tết has been a journey and a concerted effort. For many immigrants and children of immigrants, something as seemingly basic as celebrating the new year can be an expression of how we navigate our multiple cultural identities.

Growing up in the U.S. in the 1980s and 90s, I was taught to call Jan. 1 as “New Year.” Back then, my parents, like many other immigrants, emphasized that I speak only English so I could assimilate and succeed in school. I stopped speaking Vietnamese once I entered kindergarten and I didn’t start learning again until after I graduated from college. It’s not like now where many parents are clamoring for their children to be bi-and tri-lingual.

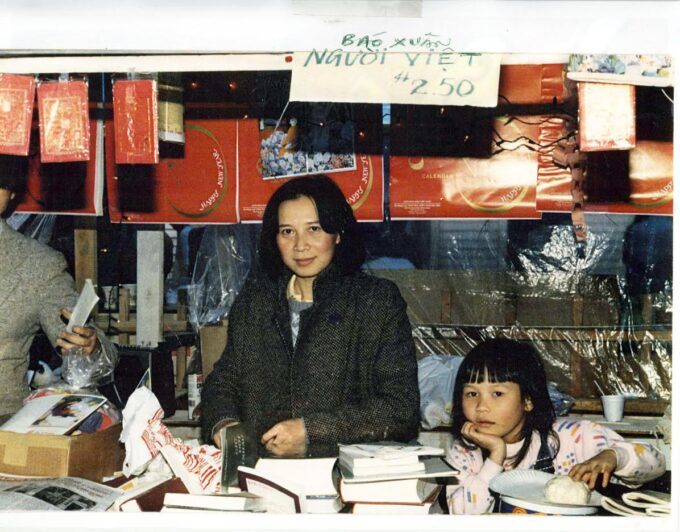

As a child, I knew it was Tết time by trays of special Tết candy and the red envelopes of lucky money I got from relatives and my parents’ friends when I bowed and recited the special Tết greeting. Since my parents ran a Vietnamese newspaper, they were busy tending to their customers’ Tết needs and we didn’t have time to observe other Tết traditions.

I witnessed Tết in Vietnam for the first time in 2003 as a grad student living in Hanoi. My Vietnamese language skills were still mediocre at best back then. I say “witnessed” because I didn’t actually experience it. Tết was a time of great rest and quiet; everything shuts down so that people can be at home with their families for up to a week. Because I wasn’t close to any local Vietnamese to be invited to their home, I spent that Tết alone. For other expatriates living in Hanoi, Tết meant the inconvenience of closed stores and restaurants. For me, I was curious because I knew people were celebrating inside and I longed to be part of it.

In the following years, when I lived in Europe, I sought out Vietnamese living or studying abroad to celebrate Tết with. To celebrate this holiday, Vietnamese say “ăn Tết,” which literally translates to “eat Lunar New Year.” There’s a lot of traditional dishes people only eat during Tết. I ăn Tết with other grad students in Aix en Provence, in Paris, in Cambridge.

My best year for ăn Tết was in 2008, when I returned to live in Hanoi. By then, I could speak Vietnamese fluently, I had established different circles of Vietnamese friends, and I was invited to numerous people’s homes. There is a traditional meal — boiled chicken dipped in salt, pepper, and thinly sliced lime leaves; Bánh Chưng, Bánh Tét made of glutinous rice, mung bean, and fatty pork; bamboo shoot soup; and ham wrapped in banana leaves. I would eat this again and again. At the start of that season I went to one friend’s home where I watched the men butcher a pig in the morning, followed by burning off its hair, and the women made the freshest ham I’ve ever had later that same day. I went with another family to make their trek to worship their ancestors at a cemetery. I drove from home to home on my moped, in a rain suit normally worn by men, feeling the whip of the wind and rain during one of Hanoi’s coldest winters. I ăn Tết in a small apartment where a single mother lived with her daughter as well as a four-story home where four generations lived and every household size and shape in between. I must have “eaten” Tết with eight to ten families that year.

When I moved back to Seattle in late 2008, I attended local community celebrations like Tết in Seattle at the Seattle Center and Chùa Cổ Lâm, the biggest Vietnamese Buddhist temple in Seattle, with a midnight fireworks show that went on for a good 45 minutes. I invited non-Vietnamese friends to join me and to learn about my culture, even if it was one that I had only recently discovered for myself. My parents celebrated by going to church. I hosted Tết for Vietnamese friends studying abroad in Seattle.

I started to adopt some Tết traditions, like making sure my home and office space was super clean before the holiday started and passing out lucky money to my friends’ children. My family set aside time for a special dinner to celebrate Tết, though we didn’t eat the traditional foods. None of us actually enjoy more than a few bites of Bánh Chưng. I organized Lunar New Year potlucks for my Asian American friends.

Although I grew up in Seattle with its large Asian population, I only began to appreciate the most important holiday to many Asians as an adult.

I had some Asian friends whose parents strictly observed Lunar New Year, and as a result they had more seamlessly bicultural upbringings where they thoroughly experienced their heritage as well as mainstream American culture. There were other Asians I knew who only celebrated their own traditional holidays and rejected holidays like Christmas, usually for religious reasons.

Some people carried on the traditions they learned from their parents. Others, like me, found a way to adopt and reclaim traditions later on in life. For many of my fellow Asian Americans, how we celebrate Lunar New Year represents one way to express our relationship with our Asian-ness in America. It reinforces how fortunate I am to have two New Years.

This Feb. 12, there were no fire crackers, no Lion dances, no food festivals in Chinatowns and Little Saigons across the U.S. None of the telltale signs that signal Lunar New Year is here. Now, with the quarantine, this year’s Tết was more like the Tết I experienced when I first lived in Vietnam in 2003: quiet, simple, a time of rest, a focus on family.

Except this time, I know I am already on the inside. The spirit of “Our New Year” is celebrated within us.

Julie Pham (Hoài Hương) – NVTB